|

Number 2. May 2016: An Anonymous Engraving of 1737

|

|

|

|

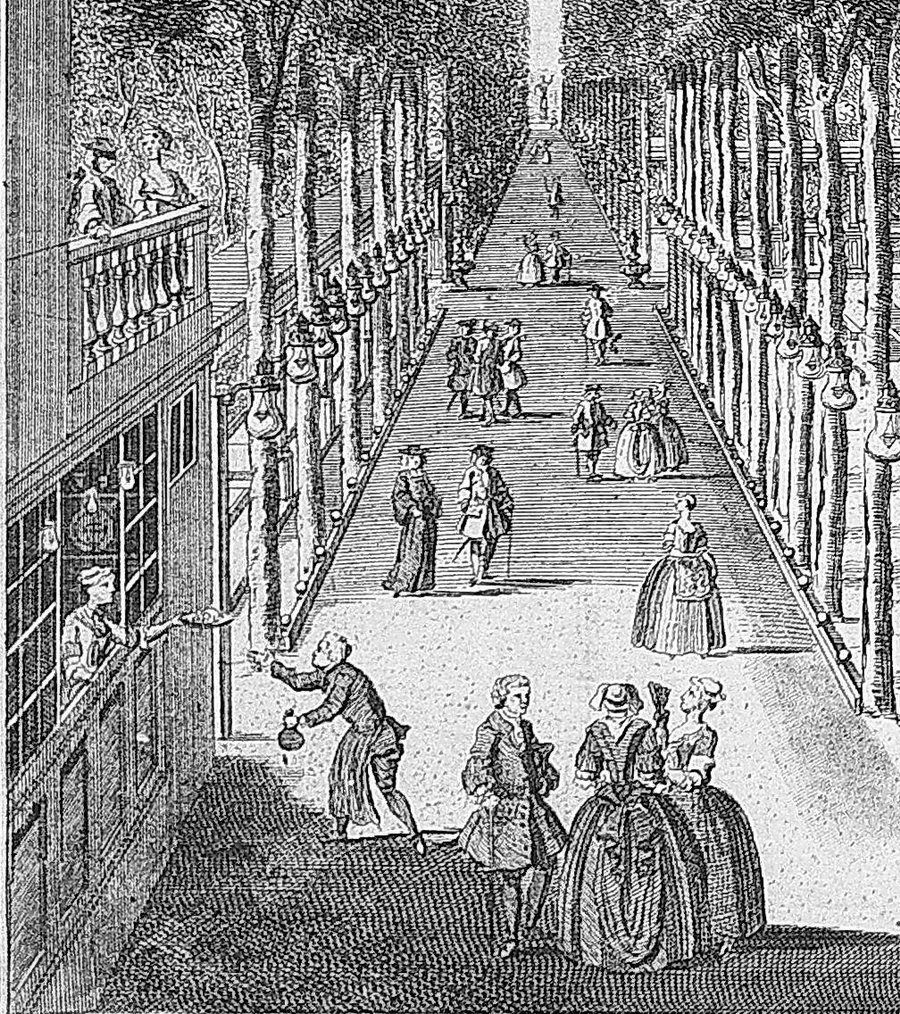

Vaux-Hall Spring Gardens (1737), Anonymous Engraving, [see p.60 and fig.36 in Vauxhall Gardens - a History] |

| Last month's object represented the very end of Vauxhall as a classic pleasure garden; this month's looks back to the re-launch of the New Spring Gardens by its new proprietor, Jonathan Tyers, more than one hundred and twenty years earlier. It is an engraved view of the Grove at Vauxhall, as seen from its western edge, made by an unknown engraver in 1737 |

| Aside from its real historical interest and relative scarcity, the thing that really sets this fascinating engraving aside as special, indeed almost unique, is that, unlike almost every other topographical print of the gardens, it was produced totally outside the influence or control of Jonathan Tyers. As far as I can tell, this is a perfectly straightforward view, with no satirical or even disapproving content at all, even though it was to be used as the frontispiece for a satirical pamphlet. |

| The pamphlet for which it was produced mercilessly lampoons not only Tyers's visitors, but also Tyers himself, and his friends and colleagues. The text of A Trip to Vaux-Hall; or a General Satyr on the Times. With some Explanatory Notes, by Hercules Mac-Sturdy, of the County of Tiperary, Esq. [for the full text on this website, click here ], is no gentle bit of fun designed to whet the public's appetite, of the sort that Tyers might have encouraged; it is a savage attack on what the pamphleteer sees as Tyers's hypocrisy, on his restriction of John Bull's jealously valued liberties, and on the sexual delinquency of contemporary Londoners. |

| The pamphlet graphically describes and ridicules the various parties of visitors being ferried across the Thames in small rowing boats, to spend their evening at Vauxhall Gardens, or the 'Spring Gardens' as it was still occasionally called. The narrator, himself one of the crowd, takes two prostitutes with him, one who sees it as just another regular job, while the other puts on the airs and graces of a grand dame. During their evening at Vauxhall they will 'hear the Fiddlers of Spring-Gardens play' and 'see the Walks, Orchestra, Colonades. the Lamps and Trees in mingled Lights and Shades.' |

| Looking at the frontispiece as a whole, starting at the left-hand side, we see, for the first and only time, the main servery and bar, immediately inside the entrance. Then the diminishing perspective of the Grand Walk, with the gilded statue of Aurora some three hundred yards away at the end. To the right of the Grand Walk is the central 'Grove', with the new Orchestra in the middle. Around the Orchestra, many tables can be seen, with bench seats, or 'forms', where visitors are partaking of refreshments. On the right is the Grand South Walk, running parallel with the Grand Walk. At the outsides of these walks, and behind the Orchestra, forming a rectangle around the Grove, are the colonnades, in which there are further tables and benches. These would later become the famous supper-boxes, but at this time, although roofed over, they were still open on all sides |

| Everywhere we look around the Grove - on every tree, in the Orchestra, in the colonnades, over the servery, on lamp-posts, there are glass oil-lamps. The literature tells us that there were some five hundred lamps at Vauxhall at this time, and the number increased every season, so that, by the time the gardens closed, this 500 had grown to around 30,000. The Vauxhall illuminations were always one of the great attractions of the gardens. The Vauxhall evening began at 5 or 6pm., in daylight, when it might attract young families with children, older visitors, and those of a nervous disposition. As it was getting dark, usually some time after 9pm, the lamps, having been prepared earlier in the day with full reservoirs and with long wicks of cotton-wool dipped in saltpetre and spirits, would all be lit within a minute or two by the proverbially fleet-footed lamplighters, and the gardens would 'instantly' be bathed in a warm glow, which could be seen for miles around - one of the wonders of the time. After the lamps were lit, the gardens became an altogether more dangerous place, and Vauxhall's clientele would undergo a subtle change, with the respectable and the very old giving way to a youthful and exuberant crowd, whose aim was to experience romantic or amorous intrigue and adventure, often in the unlit 'Dark Walks'. |

| That alteration to the character of the gardens has not yet quite happened in our print - it is still daylight, but the shadows are lengthening, and the waiters are beginning to serve suppers. The children and their grandparents have already been sent home to bed, leaving the field to the main targets of 'Hercules Mac-Sturdy's' satire - the middle-aged middle-classes. On the right, in the foreground, a tall waiter carrying a bottle and plate is being ogled by a matronly lady in the centre, possibly Mac-Sturdy's 'My Lady' who knows that their son-and-heir was not fathered by My Lord, but by her footman; she really wants to be with 'honest Saul' in the footmen's room, but 'barr'd from thence, she turns her View, on the smug Waiter, with his Apron blue; the painted Tin upon his rising Crest, Pleases her Sight, and warms her am'rous Breast.' The enamelled identification badge (or 'painted tin') that he wears on his chest is, to My Lady, much more alluring than the Garter Star worn by her Lord, himself busily engaged in flirting with the two young ladies behind the waiter (fig.2). |

|

|

Fig.2

|

| The pamphleteer's most acerbic wit is reserved for the man who re-invented and re-launched Vauxhall as a classic pleasure garden only five years earlier, and his friends and colleagues. The young entrepreneur Jonathan Tyers and his wife Elizabeth had taken on the lease of the New Spring gardens, Vauxhall in 1728, when it was little more than a popular rural tavern. They had completely transformed it, turning it into a fashionable retreat from the town, where anybody who could afford the one shilling admission could come for a civilised and relaxed evening out, with good music, good food and wine, and good company as the entertainments. The music and company were free, but the refreshments were astronomically expensive, and were the source of Tyers's profits. |

| Jonathan Tyers, though, had a strong moralistic streak, and his apparent 'cleaning-up' of the gardens was well publicised. However, as a brilliant and acute businessman he knew that single young women in his walks and groves would not fail to attract single (and not so single) young men, so he was happy to allow his pleasure garden to be used as a place of business by London's prostitutes. His closest friends were the Fielding half-brothers, Henry the novelist, playwright and barrister, and John the famously strict magistrate. It was possibly at the Fieldings' prompting that Tyers set up a force of constables to keep order at Vauxhall. Part of 'keeping order' involved protecting innocent young ladies from being importuned for sexual favours, but did not, of course, include throwing out all the prostitutes, so 'Hercules Mac-Sturdy' suspected some hypocrisy here, and attacks it with some venom. Having disposed of Tyers's other ridiculous and morally lax visitors, he fixes his eyes upon 'a Man of Worship' or magistrate, presumably blind John Fielding himself, often the target of satirists: |

|

Who

runs a-muck, and worries Men, as Curs Sheep.

|

|

Who

gets by daily Warrants daily Bread,

|

|

The

Benches Honour, and his Neighbour's Dread.

|

|

Emblem

of Justice! ruling in the Dark,

|

|

Who

neither reads nor writes but sets his Mark

|

|

And

leaves all learned Drudg'ry to his Clerk.

|

|

This

Man who traded once in Soap and Candles,

|

|

Now

all the Business of his Parish handles,

|

|

Handles

indeed! but roughly you may say,

|

|

And,

to increase his Wealth, makes Beggars pay.

|

|

No

Stocks nor Whipping-Post but can declare

|

|

His

Mercy to all Wretches in Despair.

|

| Our pamphleteer has, here, (maybe to avoid a libel case) conflated two people - blind John Fielding 'ruling in the Dark', and Jonathan Tyers himself, who 'traded once in Soap and Candles.' Tyers's family were fellmongers, treating raw hides and skins from the slaughterhouses of London to prepare them for the leather trade. The fellmonger's most profitable by-product was tallow, widely used in the manufacture of soap and candles. |

| Mac-Sturdy continues in a similar vein, to attack Tyers's constables, widely viewed as putting an unwelcome restriction on the much vaunted and long-defended liberties of John Bull to do exactly as he wanted: |

|

What

Grizzly Forms are these, who Centry stand,

|

|

With

glouting Looks, and Mopstick in one Hand?

|

|

Priests

of DIANA, set to guard the Grove

|

|

'Gainst

VENUS and her Son, the God of Love:

|

|

For

such the furious Heat of English Dames,

|

|

And

such the Swains ungovernable Flames,

|

|

That

yet they any how but under Shelter,

|

|

Shameless!

they'll all go to it helter skelter.

|

| The constables were not, in fact, there to stop young and hot-blooded English men and women from indulging themselves in any way they wished, merely to protect those who were not inclined to 'go to it helter skelter', and to prevent other visitors from being offended by sights they did not wish to see during a civilised evening out. These constables were probably the first effective force of law that the public had ever encountered; Tyers was no doubt encouraged to employ them by the Fieldings, maybe even as an experiment to see what the public reaction might be, before they instituted a similar force in the streets of London. It is likely that most ordinary visitors were reassured by their presence, but, in fact, Vauxhall's visitors were famous for keeping order amongst themselves - something that always astonished foreign tourists. Any disorder would be dealt with discreetly by other visitors, and the offenders, if necessary, ejected from the gardens, or held in Tyers's lock-up until they sobered up or calmed down. But Tyers's constables did not limit their activities just to the gardens - given the right evidence, they would track down pickpockets and other offenders throughout London |

| After lampooning wealthy lords who never paid their debts, or modest young ladies who grew less modest on the river-crossing, or the high prices of Tyers's refreshments, 'Hercules Mac-Sturdy' picks up on previous satires on Jonathan Tyers's insistence that his pleasure gardens were not about luxury or unalloyed pleasure, but rather about educating and civilising his visitors; so Mac-Sturdy, with heavy irony, compares 'Lambeth-Marsh' to the academies of ancient Athens and Rome. |

|

|

Fig. 3

|

| The engraving, though, appears to have little to do with the satirical pamphlet for which it acted as a frontispiece. I can discern only the mildest ridicule, and no hidden meaning - even the figures of Jonathan Tyers and his wife, looking down on the scene from the balcony over the servery, are no caricature [fig.3]. The whole composition could be an advertisement for the gardens. All the good points are shown - the music, the smart company, the refreshments, the walks and colonnades, and the hundreds of lamps; nobody is misbehaving, no constable is apparent, nobody's pocket is being picked, all is calm and tranquillity. The noisy, smelly, dangerous streets of London are a million miles away. Jonathan Tyers would have been delighted, until he read the text. And maybe that's the point - the contrast between the frontispiece and the satirical text is shocking, even today; the one is the impression that Tyers wants to give us, the other is what's really happening just below this apparently civilised veneer - a remarkably sophisticated and modern piece of satire. |

| [If you would like to comment on this article, please contact me] |

| Back |